Ya’nan Wang, an economist, the translator of “Capital” by Marx and Xiamen University principal had a lecture to the young teachers, asking them who were engaging in scholarship to sink their hearts to read a classic work in their own field. Principal Wang was an experienced person and his view made sense. Young people who wanted to be successful in the scholarship should not be satisfied with only reading the text books. They should dare to contact the classic books in their specialty in order to stand on the high position and have a far sight. There was a bookman of Qing Dynasty called Zhangju Liang, who advised to read intensively one book. He said “whether the book is big or small, if you are well up in it, and understand it between the lines, it is indeed a root, which can help you to comprehend other books by analogy.” What were the classic books of the English language and which one was suitable for me? No specialist instructed me. I thought I should buy a new-published original book, the thicker the better, which I thought must be a classic one. The accountant of Mapo Middle School told me that the school had just be founded and there was no library but there was some fund for books. He added that I could buy some books of English I liked to read and get reimbursed after the principal signed on the invoice. The books belonged to the school and I could borrow to read. One time I went to Nantong, stopped in Nanjing and paid a visit to the foreign language bookstore to find a classic book of the English language which I would spend years reading. I didn’t want to be engaged in the literature and had an interest in an original book useful to my teaching basic English. In the end I found a large yellow one with 1120 pages, whose first author was Randolph Quirk, a professor of London University. The title of the book was “A Grammar of the Contemporary English Language” (GCE). I hefted it, trying to find its weight and thinking it would take me a few years to finish reading it.

I began to use my best time to read it. Every morning, when it was still completely still, I got up and felt my brain was most sober, which ensured me to read something complicated. In the summer the day broke early and I carried my small table out under the tree; in winter, it was pitch dark in the morning and I went to the office, reading in the electric light. Since my reading began, I was determined from my heart, not to give up halfway. As the proverb says it is easier said than done. I met with a lot of difficulties I could not imagine before in persevering in reading the book.

The first, I had no dictionary to look up the strange words or vocabularies appearing in the book. I had only a copy of “Concise English-Chinese dictionary”,which could provide me with little help in reading such a classic work in such depth. Fortunately, I came to know some of the new concept words after a period of comparing and study of the word formation, and traced some rules about the Latin prefix, suffix and the stems which Randolph Quirk used to form special new terms. I encouraged myself and thought even if I had enough tool books I could not find the new concepts in them either.

The second, I could not understand many long sentences appearing in the book. Because of limited reading experience I had never met with such long sentences, one sentence, 10 lines, even 20 lines, even forming a whole paragraph. I first tried to get to know the general meanings of the strange new words, wrote down the sentence and posted it up on the wall close to my office desk in order to look it and to think it over again and again. After carrying on several dissections I suddenly saw a light in my brain and understood the main structure and the modifying parts of the sentence, which I felt completely reasonable. When it came to this point of time, I felt especially excited and thought that I could read and understand what ordinary English learners could not get to know, adding to my confidence to continue reading.

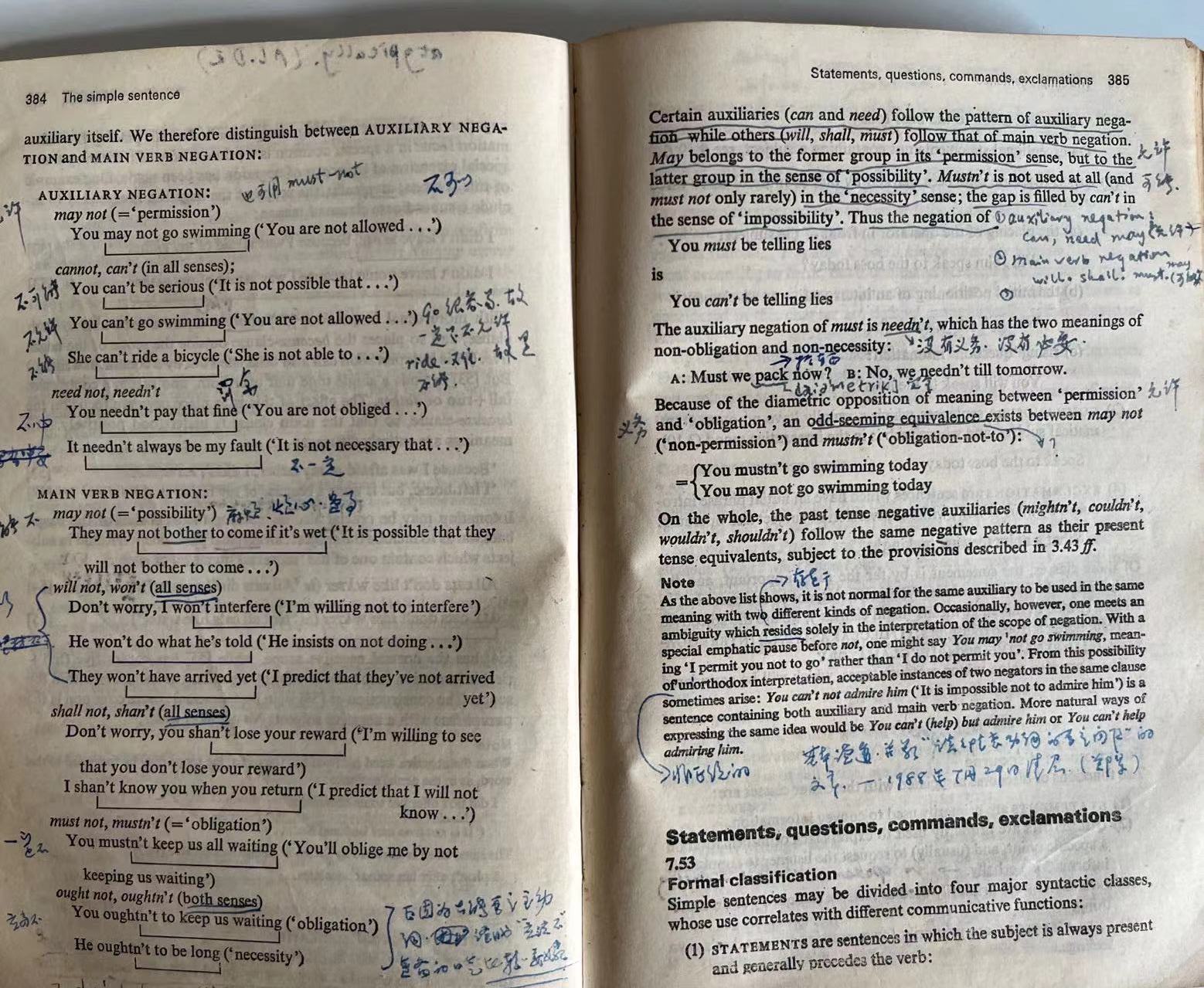

Notes made on “A Grammar of the Contemporary English Language” (GCE)

The third, the speed of reading was too slow and made me very impatient. Every morning I spent one and half hours reading and three to four mornings saw me reading on the same page, still leaving problems to be solved. I did accounts and discovered that I had to read 2160 days, i.e. about six years before I could finish such a thick book of 1080 pages, main content and three appendixes, which filled me with horror. The master of the English tongue, Bacon said in his essay “on reading”, that he saw a lot of thick books in the second-hand bookstore, “the first twenty or thirty pages of which had their margins filled with penciled notes and there were dozens of words and phrases underlined. The reader starts out, full of hope and determination. Then the need to turn to a dictionary or a reference book, perhaps ten or even twenty times a page, tires him out.” I was feeling genuinely afraid that I would follow those readers’ same old road to ruin.

The fourth, frequently I doubted whether I could get the reward from such a laborious work. I often asked myself whether one was sure to succeed if he or she read a lot. Reading was not equal to success although they were related to each other. I could only believe in whoever read a lot would be more likely to succeed. When I was reading the huge works by Quirk in Mapo, I could not combine it with the practical teaching practice because at that time in the junior or senior middle school, the English text books had only 300 to 400 words and the grammar was also very simple. I warned myself of impatience. More haste, less speed. The key problem was to completely and truly understand the essence of the book, which would make me produce respected ideas. I wrote the admonition about reading by Xi Zhu, who was a famous Confucianist of Song Dynasty, on the flyleaf of the book: “Peel the skin and you can see the meat; pick out the meat and you can see the bone; break up the bone and you can see the marrow.” I was determined to practise the spirit of dripping water wearing through rock, overcome half-hearted shortcoming and give up personal gains and losses, persevering and trying to succeed.

In my reading notes were written a lot of sentences about persistence and many a little making a mickle, such as: rope can saw off the wood, and constant dropping of water can wear away a stone. Great oaks grow from little acorns. The big tall tree comes from an inconspicuous sapling and the high building is built from the base. A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step (He who would climb a ladder must begin at the bottom.). Sand gathered constantly can become a tower. An excellent horse cannot jump a ten steps but a dobbin can go very far for 10 days whose success is attributed to its perseverance. Diligence is the path to the mountain of knowledge; hard-working is the boat to the endless sea of learning. I was determined to put these admonitions into practice, overcome difficulties with indomitable will, finish reading GCE, and know its essence. I hoped that I could do something known in the field of English teaching in the Tongshan County in several years and this small sapling of me will grow into a big tree with its mind in the blue sky and its affection deep in the fertile land.

The Chinese idiom “Constant dripping wears the stone” was my favorite. One drip of water is powerless, but steady drips are so powerful that they can wear the stone if they drop constantly at a target. In the Taiji Cave of Guangde, Anhui Province there is a lying stone in a shape of a rabbit, in the middle of which there is a hole, smooth and glossy. How is the hole formed? Over it drops of water are falling down continuously from the stone chink, always at the same point. Hundreds of years, thousands of years and even millions of years having passed, dripping never gives up, cutting and polishing, and finally has worn the hole. As a result, it has become a fantastic wonder in the Taiji Cave. If we have the spirit of dripping, with the target in our mind, persevere in what we want to do, we are sure to manage whatever we want.

Reading a professional works is not reading a novel. The latter is in pursuit of the plot and you can read 10 lines at one glance while reading a thick professional work, you can sometimes only read one line in days and must be very patient. Those with arrogance and rashness cannot manage to do it. The whole period of being a student was though rather long, the competition being only the result of the examination. The struggle of one’s whole life is like a marathon race and needs physical and will power for it. The victory belongs to those who have reserve strength.

Different from studying in the school, you can be a master of reading the thick professional works. In the school you must do what the teacher stipulates for you. You have to get ready to be examined by him or her. The time is restricted and you are completely in a passive position. Teaching yourself, you can keep calm and your aim is to understand what you read. You can adopt what the ancient scholar said, “Read without understanding and you can think; think without the result and you can read.” Again and again you are sure to understand what you’ve read and advance forward slowly.

It took me indeed more than six years to finish reading the CGE for the first time, every page with my notes, avoiding sharing the fate of most students. “At the first pages of a thick book you can see some notes the reader has written,indicating the reader’s hope and determination. But in the later pages the margins are empty, indicating the reader does not touch them.” After the first time of reading I had a rough impression of the CGE and there was some amount of half-cooked rice. It was a long way to go to reach the standard put forward by Master Xi Zhu. I began to read the CGE for a second time, which took me one and half years. Generally speaking, my feeling changed a lot, realizing the transform from “gnawing at a bark” to “enjoying the fragrantness of the plum blossom coming from the cold winter”.

It was pleasing when you could understand what you read, but understanding was still not the purpose, we must solve the practical problem with what we had understood. The gap between understanding and applying was somewhat wider than that between reading and understanding, which I would express in detail in the following sections.

Nov. 15 2008 in Melbourne

Proofreading Feb. 9, 2012, in Chicago

Uploading Aug. 4, 2023, in Xuzhou